Cody Sheehy and Samira Kiani on Make People Better

Courtesy of Cody Sheehy

In its first scene, Make People Better gets the viewer to get closer to the action. It starts outside in a lowly lit factory in the evening in Shanghai with few distinguishable features besides a couple of machines. Then, audio from a phone call plays between the film's featured scientists, Ben Hurlbut and Jiankui He, where they have some vague communication within the shots of the factory and the city. Once they reveal He's situation, quick shot transitions of science and news footage create a chaotic high, adrenaline thriller for the audience.

Following continuing discoveries of environment and evolution in their documentaries, Cody Sheehy and Rhumbline Media add Make People Better to their body of work. It follows scientist Jiankui He's findings on genome editing human embryos. Having access to the top experts in different environmental and technological fields, he brings scientist Samira Kiani to the film as a producer. In addition, they collaborate on getting Kiani's connections, such as He, his colleagues, and scientific accuracy to the film.

Make People Better will make its world premiere at the 2022 Hot Docs Documentary Film Festival (April 28 - May 8). Sheehy and Kiani recently sat down with me via zoom before its screening about Gattaca’s influence towards gene editors and other human genealogists, the film’s structure, and the future of human genealogy.

- NOTE: This conversation is edited & condensed for clarity. -

EF: I just want to say that your film shows a lot of historical patterns of human genealogy and when did you decide to tell this story, Cody and Samira?

CS: So, the way the story really unfolded for me is I got a phone call from Samira. Samira is a genetic engineer. She called me and said there is a lot of things going on in the genetic field that the general public just has no idea about. It’s gonna be a revolution. It’s gonna be like the internet changing everything and we should make a film on that. So, we started on this journey and it took about 5 years. The story of Jiankui [“JK”] He and the first genetic babies, we didn’t even know that was gonna happen. So that happened two years into the process and everything that we have been following. There were many stories. This film could have been about amortality. It could have been about how we’re gonna totally transform nature with these technologies. It could have been a lot of things. But when the first genetic babies happened, that just really focused us. The story just sort of told itself and we were there at the beginning of it and were lucky to have that opportunity and followed it.

EF: Okay. As you mentioned that you were filming for five years, I was wondering how you filmed JK’s interview [before this statement]. How were you able to schedule his appearance, as well as the other featured scientists such as Ben Hurlbut and Ryan?

SK: As Cody mentioned, it was like a process. Two years before meeting JK, we had built up all these connections and interviews. We didn’t know that we would find the first gene editors of the babies. So we had all these connections. Because I also was fortunate to be part of the scientific community, I had these networks previously that I knew that they were interested in the topic. So we scheduled the interviews and everything. With JK, obviously as you know the moment that the news broke, he got into custody, we didn’t have access to him. But through the people who had close contact with him [such as Ben and Ryan] could have access to some of the materials from him and used it in the film.

CS: When JK was under house arrest, he had a window of time where he could reach out to the West, to tell his story and that’s what he decided to do. He knew he wouldn’t be able to tell it in China, that’s when he started a series of conversations with the main character of our film Ben. Those stories were captured as part of our film and we’re very lucky to be a part of the network that Samira mentioned. Some of the other materials were filmed by Ryan, who worked with JK and was around him. They were actually filmed before he disappeared.

EF: As you said that there’s a lot of safety and protections in this film. How were you able to keep Ryan’s identity [and the film’s featured undisclosed locations] safe?

CS: Ryan was very worried about his identity and the consequences of revealing all of this. We went to great lengths to make sure that all of our phone calls were happening on secured lines that couldn’t be listened to. We had other people to protect too. Some of the most important people in the film that we decided to protect early on were the babies themselves, Lulu and Nana. They are innocent twin girls and to reveal their location or anything like that could have effects on their life. That was an important thing for us to do to also protect them and other people also.

SK: It took a year to build enough trust with other people. Not with Ben, at least with Ryan, to be able to actually achieve that. We had to really go back and forth and make sure he feels confident to work with us. So it was a process that we got through.

CS: Like all documentaries, it pivots on trust. That’s what we had to do is to build trust.

EF: I do want to talk about your inclusion of Gattaca in the film. Can you talk about your impressions of it before and after the making of the film.

SK: Well for me [before being a scientist], the invent of after genetic technology of it all. Obviously Gattaca was something else, science fiction, lol. After genetic editing, I was like oh wow, this is gonna happen. So what the reference is that Gattaca has in the movie, it is something that is close to really happening at least in the next 25 years. So doing the film and witnessing what is gene editing now, movies like Gattaca, they aren’t science fiction anymore, they are close to being science fact.

CS: It is amazing how the great science fiction out there often inspires or creates the science that then follows it. Then that science then that science inspires the next generation of science fiction writers. Gattaca, I think, is a great example of a film that was totally prescient. We included it in our documentary because it’s accurate and they were 25 years ahead of the technology being real, but they predicted it perfectly of us and it’s certainly amazing.

EF: Well, art is imitating life.

CS: (chuckles)

EF: At times, the film feels like an investigative and a science non-fiction movie. How did you find the film’s structure when you were editing it?

CS: That was really an important part of our process. [Featured MIT Technology Review journalist] Antonio [Regalado]’s investigation brings a lot of energy to the film. It re-engages with the audience each time. Weaving that in with JK’s story which is moving slower and more methodically towards when the babies are born and released. We wanted to come to Antonio at the right times, just really keep the film moving and keep it from getting it bogged down with too much of the science [information]. That was an important back and forth that we did. By Act 3, we just wanted to blow up with everything that you felt about JK and you felt about the story. We wanted to turn that on its head as we pulled back the curtain.

EF: What were some surprises both of you encountered within the history of human genealogy during the making of the film?

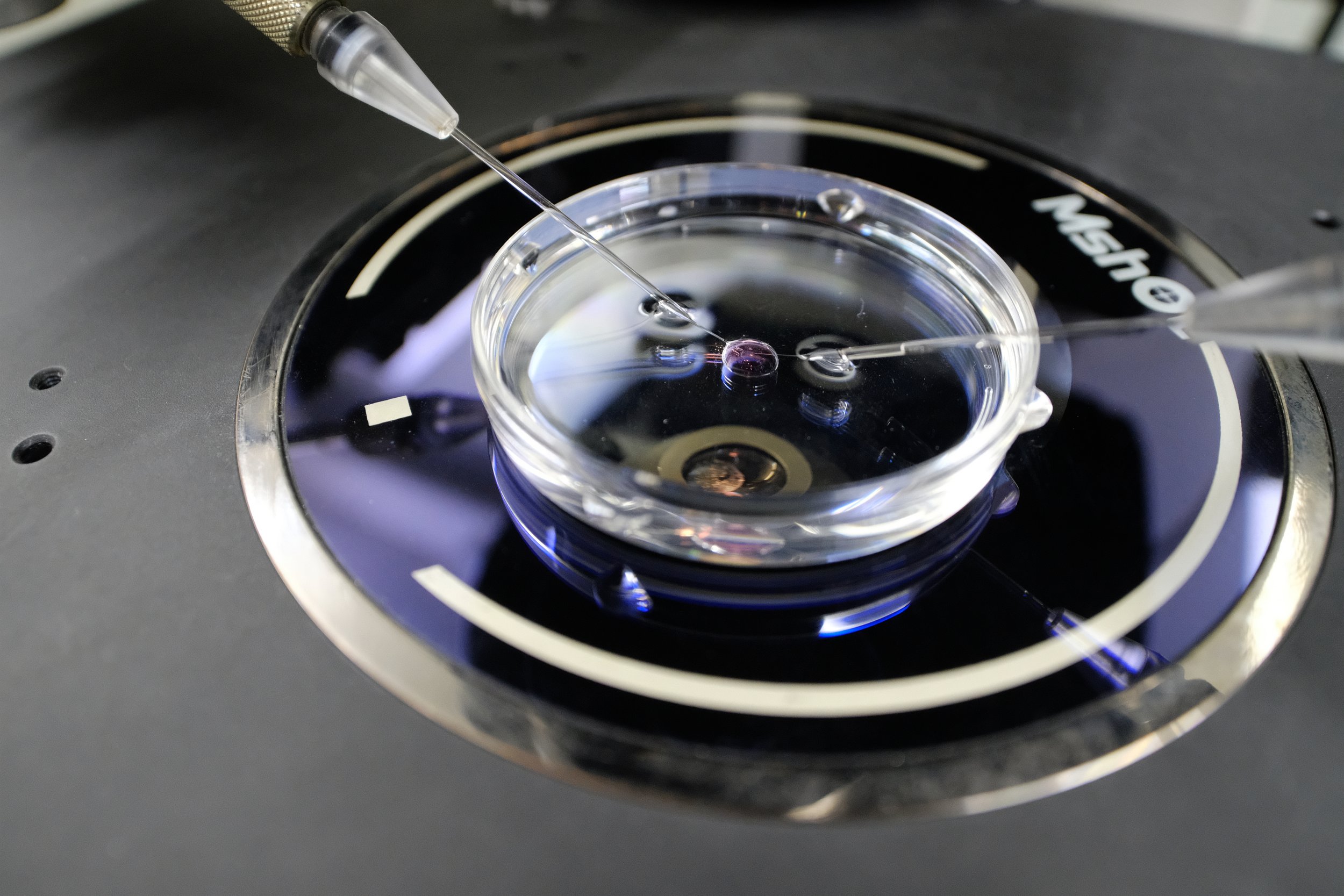

CS: As we started to really research the IVF and the fertility industry, there has been a reason since that first experiment that we show in the film. It is very similar to what JK did. They did something that was way ahead of what was accepted at the time. They released it to the media. It is a similar story and now that industry is massive. We learned that 1 out of 85 babies are now born with IVF. It has really changed all kinds of things about having kids, including how long you can have them in life. To me, that was pretty amazing to learn about how much that industry has grown, how much money is involved in it now.

SK: I was just thinking about that. I was thinking that a lot of things that happen over the experience were something that we were predicting to have in the science field. For me, to see that they are actually happening. It was not just surprising, but more like eye-opening or terrifying in a way like wow, we carry tremendous responsibility for the future generation and I think that was something that struck me, like, okay we are not just scientists anymore. WIth these tools that we can manipulate biology. We have greater responsibilities right now.

EF: As you say you’re carrying this for the future generations, where do you see the future of human genealogy or embryos? I understand that Cody is not a scientist while Samira is. I will like to have a scientist and a non-scientist perspective on it?

CS: I have gotten a crash course during the making of the film. One of the things I believe will probably happen as these technologies become safer and more commercialized. There’s a chance that mothers and fathers out there when they have their kids, will feel an obligation to make sure those kids could be as healthy as they can be or as strong as they can be. If everyone is doing it, there’s gonna be pressure on you to also spend $5,000 or $10,00 to make a change that could theoretically make your kids' life better in some way or your perception of it being better. I think that pressure is coming for future generations. That’s my prediction.

SK: I agree. We are moving to that direction. My hope is that it will be used to treat human diseases and other devastating diseases. Also, we will be able to somehow control it or regulate it, so it won’t be used for nefarious purposes. There’s an issue of inequality of access. We want to have this technology being accessible to all. I hope that with things that we decide right now with policies that we put in place, we can come up with ways so that we can appreciate the benefits and avoid the harm. As I said, it’s a powerful technology.It’s moving forward very fast. We need to start thinking about how we redirect it to a direction for the benefit of humanity.

EF: What policies do you have in mind to create the greater good of humanity?

SK: That’s the question that we are asking for the last few years and we are starting to work about it with international organizations. The most important thing that is important for all of these things that I said is public engagement. People need to know. People need to be involved in the type of decisions we make. The type of activities that Cody and I have started to do and we continue to do alongside this film is to really build upon this engagement with legalities to bring in a lot of different people. That’s part of other things that we do in our impact campaign and other activities. One policy would be how to engage with more people and that’s what we are working on right now.